25 But although the state-interest framework provides analytical scaffolding for a welter of constitutional doctrines, no watershed opinion has set out a clear method for determining whether any given interest is compelling, important, or merely legitimate.

LEVELS OF JUDICIAL SCRUTINY FREE

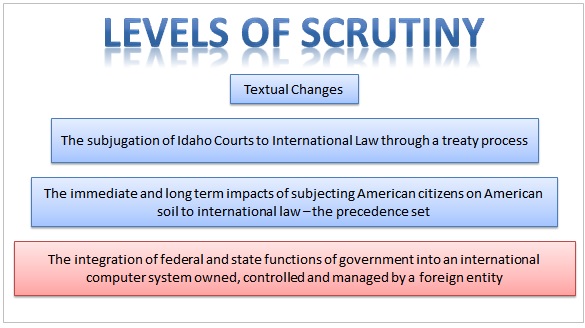

22 Finally, the Court applies an intermediate level of scrutiny - requiring that state action be “substantially related” to the achievement of an important state interest 23 - when assessing sex-based equal protection claims 24 and certain free speech claims. 21 On the other hand, state action touching select constitutional rights is subject to strict scrutiny and so must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest. Over time, the application of heightened scrutiny has resolved into a familiar tripartite framework 20: Most state action is subject to rational basis review and so need only be rationally related to a legitimate state interest. 16 A majority of the Court soon cemented this demand into free speech jurisprudence, 17 and the compelling-interest requirement eventually leaked into free exercise 18 and race-based equal protection 19 jurisprudence as well. forego even a part of so basic a liberty as his political autonomy” serve not simply a legitimate, but, still more, a compelling state interest. are susceptible of restriction only to prevent grave and immediate danger to interests which the State may lawfully protect.” 15 This ideal crystallized into the First Amendment’s demand, first articulated in a 1957 Justice Frankfurter concurrence, that state action requiring “a citizen to. 14 Soon thereafter, perhaps wary of the totalitarian orthodoxies then riving Europe, the Court began to employ just such heightened scrutiny under the Free Speech Clause, declaring in 1943 that “freedoms of speech and of press. 13 responded to this increased risk of potentially meddlesome state action by reserving the possibility that state action that impinges on select constitutional values may warrant “more exacting judicial scrutiny” than does state action otherwise. 10īut during the wax of the New Deal regulatory state, the wane of the Court’s recognition of constitutional economic rights 11 ushered in an expanded range of constitutionally “legitimate” purposes. Supreme Court’s recognition of a personal right to economic liberty under the Due Process Clause reached its apogee in 1905 with the Court’s invalidation of a New York statute that limited bakers’ working hours, for example, the Court did not impugn as insufficiently weighty the state’s asserted interests in “safeguard the public health” and the health of the bakers 7 rather, the ineffectual manner in which the statute served those interests 8 led the Court to suspect that the law was, “in reality, passed from other motives.” 9 And those other motives - economic redistribution through the regulation of private contract - were simply not constitutionally legitimate under the Court’s then-conception of economic liberty.

And up through the early twentieth century, even state action that encroached on constitutionally protected rights was lawful as long as it possessed a rational relationship to some legitimate end. 4 As Chief Justice Marshall once famously defined the scope of federal power, “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the onstitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the onstitution, are constitutional.” 5Īt both the state and federal levels, then, any legitimate state interest can in most cases provide a constitutionally sufficient justification for state action.

2 And although the federal government acts within a more restricted ambit of lawful authority, 3 it too may as a baseline proposition take any action that is rationally related to a legitimate exercise of its constitutionally enumerated powers. It is a fundamental principle of constitutional law that a state government’s police power “is one of the least limitable of governmental powers.” 1 Where no fundamental rights or protected social classes are implicated, the states may typically, within the constraints of the constitutional prohibition on arbitrary or discriminatory legislation, adopt any measure that is rationally related to a legitimate governmental interest.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)